The debate over active versus passive voice is a cornerstone of academic writing. If you’ve spent time in a secondary school English classroom, you’ve likely seen a teacher circle your “to be” verbs, demanding more “action.” The general rule is simple: active voice is punchy and direct, while passive voice can feel clunky. However, as you transition to university-level composition, you’ll find that the “rules” are more nuanced. Mastering when to strategically use the passive voice is a hallmark of a sophisticated writer.

Mastering this balance is essential for students aiming for the top of the class. If you find yourself struggling to strike the right tone, seeking professional English assignment help from experts at MyAssignmentHelp can provide the personalized guidance needed to refine your prose. Understanding the nuances of voice isn’t just about following a checklist; it’s about understanding your audience and the specific requirements of your discipline. Whether you are writing a lab report for Chemistry or a critical analysis for History, the way you structure your sentences dictates how much authority your writing carries.

Understanding the Basics: Active vs. Passive

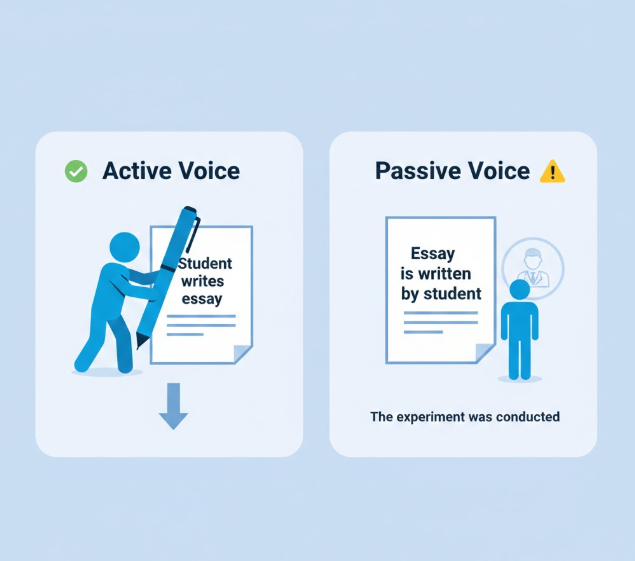

Before we dive into the “why” and “when,” let’s clarify the “what.” In an active sentence, the subject performs the action.

- Example: “The researcher (subject) conducted (verb) the experiment.” It’s direct. We know exactly who did what.

In a passive sentence, the subject receives the action, or the “doer” is omitted entirely.

- Example: “The experiment (subject) was conducted (verb) by the researcher.” Here, the focus shifts from the person to the process. In academic writing, this shift is sometimes accidental (a result of wordiness), but often, it is a deliberate choice made to emphasize results over individuals.

Why the Active Voice Usually Wins

For 12th-grade students preparing for college, the active voice is your best friend. Why? Because it forces you to be specific. When you use the active voice, you cannot hide behind vague phrasing. It helps you avoid “nominalization”—the habit of turning a perfectly good verb into a heavy noun (e.g., changing “decided” to “made a decision”).

Using active verbs makes your arguments feel more vigorous. In a persuasive essay, you want your claims to land with impact. “The author argues” is far more convincing than “It is argued by the author.” The former suggests a direct engagement with the text, while the latter feels like you’re standing across the room from your own point.

When Passive Voice is Actually Better

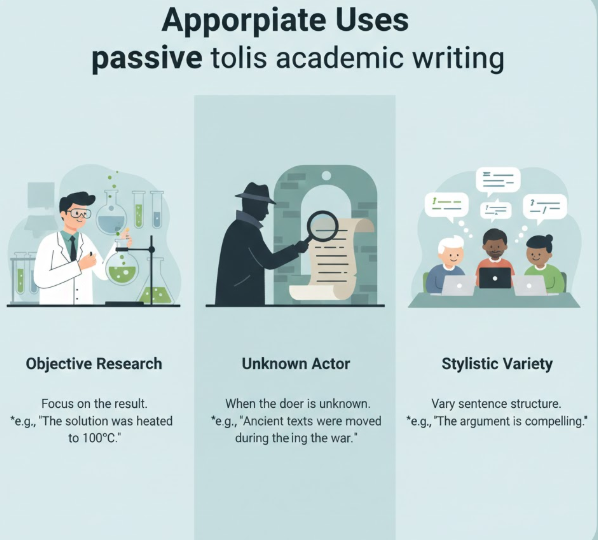

Despite what the grammar checkers say, the passive voice has a vital role in academia, particularly in the sciences and social sciences.

- Emphasis on the Objective: In a scientific report, who poured the chemical into the beaker is usually irrelevant. What matters is that the chemical was poured. Using the passive voice here creates an air of scientific objectivity.

- When the Actor is Unknown: If you are writing a history paper about an event where the perpetrators are anonymous, the passive voice is your only logical choice. “The ancient scrolls were moved during the war” makes more sense than “Someone moved the scrolls.”

- To Create Variety: If every single sentence in your 1,400-word essay starts with “The author…” or “I…”, your reader will get bored. Using the passive voice occasionally can shift the rhythm of your writing and keep the reader engaged.

Navigating Complex Assignments

As you move into specialized subjects, the expectations for your writing style will change. For instance, the linguistic precision required for writing an A-Level English Literature essay is vastly different from the style used in a creative writing piece or a business memo. In literature essays, you are often tracking the movement of themes or the development of characters. While the active voice helps you attribute actions to characters, the passive voice can help you describe the atmosphere or the effect of a literary device on the reader without sounding repetitive.

4. Strategic “Rule Breaking” in Literature and Humanities

In the humanities, your voice is your brand. When you analyze a poem or a novel, you are essentially building a case. Most of the time, you should use the active voice to show how the author uses language to create meaning.

However, you can “break the rule” when you want to emphasize the recipient of a historical or literary action. For example: “The protagonist is trapped by the societal expectations of 19th-century London.” This passive construction is actually more effective than the active version because it emphasizes the protagonist’s lack of agency—the fact that they are being acted upon.

5. How to Spot “Accidental” Passive Voice

The “bad” kind of passive voice usually happens when a writer is trying to sound “smart.” Many students think that long, complicated sentences are a sign of intelligence. In reality, the smartest writers are those who can explain complex ideas simply.

Watch out for these “Red Flag” phrases:

- “It was found that…” (Just say “We found…”)

- “There are many examples of…” (Just list the examples.)

- “A decision was reached…” (Just say “The committee decided…”)

If you can replace a “was [verb]” with a single, strong action verb, do it. Your grade—and your reader—will thank you.

6. The “By Zombies” Test

A fun and easy way to identify the passive voice is the “By Zombies” test. If you can add the phrase “by zombies” after the verb and the sentence still makes sense, you are using the passive voice.

- Passive: “The city was destroyed [by zombies].” (Makes sense.)

- Active: “The fire destroyed [by zombies] the city.” (Does not make sense.)

Once you identify it, ask yourself: Is the person doing the destroying important? If yes, rewrite it in the active voice: “The Great Fire of 1910 destroyed the city.” If the focus should stay on the destruction itself, keep it passive.

7. Adapting Your Voice for Academic Standards

Across global higher education—from the UK to the US and Australia—there is an increasing emphasis on “student voice.” Tutors and professors want to see that you have critically engaged with the material rather than just repeating facts. This shift means that in many disciplines, the active voice is preferred because it demonstrates ownership of an argument.

However, a common pitfall for students is confusing “active voice” with “informal opinion.” Even when “I” is permitted, your authority comes from your evidence, not just your presence.

- Weak Active Voice: “I think the author’s conclusion is wrong.” (Too personal/informal).

- Strong Active Voice: “The author’s logic fails to account for…” (Authoritative and direct).

This level of writing earns top marks (or a First-Class grade in the UK) because it takes ownership of the claim without making the essay feel like a personal diary. It maintains academic distance while using the strength of the active voice to drive the point home.

8. Final Polish: The Revision Phase

Writing a high-quality essay is a multi-step process. Your first draft will likely be full of passive voice and “filler” words. That’s okay. The magic happens during revision.

When you sit down to edit, read your work out loud. Listen for the “is,” “was,” “were,” and “been.” When you hear them, stop and ask if that sentence could be more energetic. Could a stronger verb take its place? If you’re describing a character’s journey, are they the hero of the sentence, or is the sentence happening to them?

Conclusion

Mastering the balance between active and passive voice is like learning to drive a car with a manual transmission. It takes practice to know when to shift gears. Generally, let the active voice do the heavy lifting—it keeps your writing fast-paced, clear, and honest. Save the passive voice for those specific moments where you need to emphasize a result, maintain a scientific distance, or highlight a sense of powerlessness.

By being intentional with your verb choices, you aren’t just following grammar rules; you are taking control of how your ideas are received. Whether you are aiming for a top score in a high school capstone or preparing for the rigors of university, the clarity of your voice will always be your greatest asset.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Is the passive voice ever “wrong” in a college essay?

It is rarely grammatically incorrect, but it can be stylistically weak. In American academic writing, the passive voice is discouraged when it makes your sentences vague or hides the person responsible for an action. However, it is perfectly acceptable—and often preferred—in scientific abstracts or when the focus must remain on the result rather than the researcher.

2. How can I easily identify passive voice in my own writing?

Look for “to be” verbs (am, is, are, was, were) followed by a past participle (a verb ending in -ed or -en). A simple trick is to see if you can add “by zombies” after the verb. If the sentence still makes sense (e.g., “The data was analyzed… by zombies”), it is in the passive voice.

3. Does using active voice make an essay sound too informal?

Not at all. In fact, the active voice often makes your writing sound more professional and authoritative. Using strong, direct verbs shows that you have a firm grasp of your subject matter. The key is to maintain a formal vocabulary while using an active sentence structure.

4. When should I prioritize the passive voice?

You should use it when the receiver of the action is more important than the doer. This is common in lab reports (“The solution was heated”), historical descriptions where the actor is unknown, or when you want to intentionally create a sense of detachment or objectivity in your tone.

About the Author

Mark is an academic consultant and senior content strategist at myassignmenthelp, where he specializes in helping students navigate the complexities of university-level writing. With over a decade of experience in educational coaching, Mark focuses on bridging the gap between high school basics and advanced academic discourse.